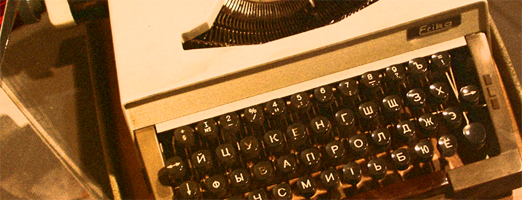

“I would erect a monument to the typewriter …” Former Soviet dissident Vladimir Bukovsky

Vladimir Bukovsky summed up samizdat this way: “I write it myself, I edit it myself, I censor it myself, I publish it myself, I distribute it myself, I sit in jail for it myself.” “Samizdat” became a familiar part of the Cold War lexicon. The neologism “samizdat,” shares with the Russian words samolet (airplane), samovar, and samogon (home-made liquor) the root sam-, meaning self. Samizdat is self-published material. Samizdat was a system of uncensored textual production and circulation that developed in the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death, and which spread in the 1970s to other Communist bloc countries, and even to China. Classic Soviet samizdat was produced primarily on typewriters. It always involved risk to Soviet writers and editors, readers and distributors before the situation changed with Gorbachev’s Perestroika and Glasnost in the late 1980s. Samizdat signified a passionate commitment to a free textual culture in the context of a repressive regime.

Vladimir Bukovsky summed up samizdat this way: “I write it myself, I edit it myself, I censor it myself, I publish it myself, I distribute it myself, I sit in jail for it myself.” “Samizdat” became a familiar part of the Cold War lexicon. The neologism “samizdat,” shares with the Russian words samolet (airplane), samovar, and samogon (home-made liquor) the root sam-, meaning self. Samizdat is self-published material. Samizdat was a system of uncensored textual production and circulation that developed in the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death, and which spread in the 1970s to other Communist bloc countries, and even to China. Classic Soviet samizdat was produced primarily on typewriters. It always involved risk to Soviet writers and editors, readers and distributors before the situation changed with Gorbachev’s Perestroika and Glasnost in the late 1980s. Samizdat signified a passionate commitment to a free textual culture in the context of a repressive regime.

Samizdat was the backbone of Soviet dissidence, according to former activist and dissident historian Ludmila Alexeyeva. Another metaphor she used to describe samizdat was mushroom spores, spreading wide to create links among people who formed unofficial networks. The human rights bulletin A Chronicle of Current Events (Moscow, 1968-1983) spread this way among Soviet readers and out to Western media. Samizdat was literature, history, art and activism forbidden by the Soviet regime. Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago circulated as samizdat. Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s uncensored GULag Archipelago appeared in the West in the early 1970s. Solzhenitsyn’s work made it impossible for Western and Soviet readers to ignore the facts about the shockingly massive and punitive prison camp system that had existed under Stalin. Many also took note of an uncensored essay in 1968 by a soft-spoken but fiercely committed nuclear physicist named Andrei Sakharov, who proposed a path toward “Progress, Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom” for all countries. All three, Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov, won Nobel prizes for their work, despite the Soviet Union’s disapproval.

In the mid-1960s, the arrest and trial of writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel caught the attention of the international press. The case involved absurd charges of anti-Soviet propaganda and it resulted in surprisingly harsh sentences to 7 and 5 years in labor camps for the defendants. The case provoked an international outcry. For Soviet citizens, the case proved to be a watershed. The public demonstration that took place in Moscow on December 5, 1965, marked the birth of a Soviet civil rights movement. At that meeting, Soviet citizens demanded openness in the proceedings against the two writers, calling on Soviet authorities to respect their own constitution. Alexander Ginzburg documented events associated with the case, along with Soviet and Western press reaction in a samizdat White Book. Ginzburg and those who worked with him were later tried and convicted by Soviet authorities for those efforts.

The demonstration of just eight people in Red Square in August, 1968, against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia showed the difficulty of organizing anything like the street protests familiar in Western countries around that time. Soviet authorities reacted brutally to the protest on Red Square. One of the demonstrators, the young mother Natalya Gorbanevskaya, subsequently spent almost two years in a psychiatric hospital. Gorbanevskaya, however, had already managed to launch the samizdat bulletin A Chronicle of Current Events (Khronika tekushchikh sobytii) in April of 1968. The Moscow Chronicle would run for nearly 15 years through the efforts of a brave and committed group of people, many of whom were arrested simply for reporting facts unavailable in the official Soviet press.

According to Sakharov, the Moscow Chronicle embodied “the best in the human rights movement, its principles and highest achievements.” The Chronicle helped usher in a whole series of samizdat publications devoted to exposing human rights abuses for an audience of Soviet citizens and Western observers alike. Chronicle editors instructed readers, who were also the volunteer “publishers” of the Chronicle, to be careful to avoid errors when they retyped issues of the Chronicle to pass along to their friends. If they wanted to send information back to the editors for an upcoming issue, they should simply give it to the person from whom they received a copy. It was too risky for the editors to publicize their names and addresses on the Chronicle. The system functioned on the basis of these networks of trust and chains of reproduction and transmission. Although some samizdat editors put their names and addresses on the front of editions to demonstrate their openness and legality, most deemed it too risky to do so.

The Moscow Chronicle and similar bulletins provided the facts about human rights issues and the problems of minority groups in the Soviet Union, including the Crimean Tatars, Jews, Meskhetians and Volga Germans, who sought the right to emigrate or to develop their own cultures and histories. We find evidence of remarkable efforts by religious groups to defend their right to practice their faith and educate their children. The unofficial Baptist movement was particularly strong. The push for national culture expressed itself with special force in the republic of Lithuania, where samizdat flourished with the help of Catholic networks. Many of these groups overlapped with human rights activists of the democratic movement in Moscow. The Chronicle reflects that alliance of various groups and interests. The Chronicle’s scrupulously dry and voluminous reporting came to life in accounts by Peter Reddaway and Ludmila Alexeyeva that provided history and context for the causes and activism behind the arrests.

Other types of activity developed in and through samizdat. Even before a samizdat system emerged, people copied out poetry unavailable in official Soviet print by the great poets of the modernist generation, Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelshtam, Boris Pasternak, Marina Tsvetaeva and others. Younger poets and artists also created work for manuscript circulation, along with unofficial readings and exhibits. One of the new poets known through samizdat beginning in the 1960s was Joseph Brodsky. Convicted by Soviet courts for “parasitism,” Brodsky later became a Nobel laureate. The development of a samizdat system encouraged such new unofficial cultural activity in Leningrad, Moscow and elsewhere. People wanted to write and create beyond the strictures of official Socialist Realism – the official mandated realistic style – and the straitjacket of Soviet censorship. The late 1970s in Leningrad saw a particularly vibrant unofficial cultural scene. Neo-futurist, and new constructivist and conceptualist work appeared in Moscow, in the provincial city of Yeisk, in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg), and elsewhere. Musicians and music lovers also made use of samizdat. There existed a parallel phenomenon of unofficial audiotape production and circulation dubbed magnitizdat. Samizdat bulletins like Menestrel and Kvadrat covered bard music and jazz more fully and for a wider audience than authorities allowed. In the early 1980s, despite efforts to repress most socio-political samizdat, a network of rock zines provided a place to find interesting journalism and distinctive graphic and prose styles.

Too often these streams of civic and cultural samizdat have been treated as separate phenomena. Socio-political samizdat garnered far more attention at the time it was created, because of the urgency of its topics. But samizdat now appears important also as a forum for the development of independent culture. With some distance from the burning issues of the Cold War, we can better appreciate the variety of voices and the distinctiveness of particular contributions to the rich culture of samizdat.

- Ann Komaromi, University of Toronto

For a Selected list of sources about Samizdat and Dissidence, see here.